Victory and Loss: Solnit’s Letter to My Dismal Allies on the US Left

Rebecca Solnit ends her letter, (though it was published, online, in The Guardian, on October 15, 2012, I’ve just run into it and find it – still – relevant for many reasons, which I’ll try to capture here), by saying the following :

There are really only two questions for activists: what do you want to achieve? And who do you want to be? And those two questions are deeply entwined. Every minute of every hour of every day you are making the world, just as you are making yourself, and you might as well do it with generosity and kindness and style.

That is the small ongoing victory on which great victories can be built, and you do want victories, don’t you? Make sure you’re clear on the answer to that, and think about what they would look like.

Solnit also says:

There is idealism somewhere under this pile of bile, the pernicious idealism that wants the world to be perfect and is disgruntled that it isn’t – and that it never will be. That’s why the perfect is the enemy of the good. Because, really, people, part of how we are going to thrive in this imperfect moment is through élan, esprit de corps, fierce hope and generous hearts.

Solnit is, for me anyway, trying to channel, (to some extent and falling dramatically short), Slavoj Žižek, the Slovanian Marxist philosopher, psychoanalist, and cultural critic. (To directly cite Žižek would be disastrous for her, I’m sure.)

I see Solnit’s thinking and language parallel Žižek’s in primarily two texts: Žižek‘s The Sublime Object of Ideology (1989), and the more recent, his Demanding the Impossible, a conversation edited by Yong-june Park (2013).

Let’s begin with Solnit’s assertion, There are really only two questions for activists: what do you want to achieve? And who do you want to be? And I agree with Solnit that these are deeply entwined questions.

In the first chapter of Demanding the Impossible, titled “Politics and Responsibility,” Žižek argues the following (and it’s relevant to see it entirely to note the parallel):

What is a common good today? OK, let’s say ecology. Probably most people would agree, even though we are politically different, that we all care about the earth. But if you look closely, you will see that there are so many ecologies on which you can have to make so many decisions. Having said that, my position here is very crazy. For me, politics has priority [underline for emphasis in original] over ethics. Not in the vulgar sense that we can do whatever we want – even kill people and then subordinate ethics to politics – but in a much more radical sense that what we define as our good is not something we just discover; rather, it is that we have to take responsibility [underline for emphasis in original] for defining what is our good.

In this sense, priority and responsibility as valuable standards by which to address the questions, what do you want to achieve? And who do you want to be?, appear to respond, in one way, to what we first need to consider if we’re going to respond to Solnit’s questions appropriately.

Only Žižek might argue that Solnit is passing from one extreme into another.

What does that mean?

Every minute of every hour of every day you are making the world, just as you are making yourself, and you might as well do it with generosity and kindness and style, says Solnit. This is a compulsion, Žižek says, for a sort of partial harmony (Demanding the Impossible); it is defining the world we live in by contrast when, what we need to answer Solnit’s questions is, first, another set of relevant – perhaps the most relevant – questions: How do we imagine individual freedom? And how do we imagine the common good?

Listen to Žižek and you see where Solnit stops short in her analysis:

The first thing I would like to do is show how absurd it is to urge that we have two extremes and need to find the balance. These two extremes already flow into each other. That is why “synthesis” does not affirm the identity of extremes, but on the contrary, affirms their differences as such. So the synthesis delivers difference from the “compulsion to identify.” In other words, the immediate passage of an extreme into its opposite is precisely an index of our submission to the compulsion to identify.

It is precisely this bind that compels us to re-examine Solnit’s proposition – generosity and kindness and style as a solution – and turn it back on itself. Generosity and kindness and style suggest that we live in a world that’s the polar opposite – not generous, unkind and cruel, without style. Of course, these negatives do come with style – maybe a style that’s harsh, brash and vulgar, but style nevertheless. This reality – or truth – puts those on the political Left, which Solnit is addressing, already on the defensive, evident in the reactions Solnit is criticizing; likewise, since those on the political Right don’t see themselves as cruel, unkind and styleless, we are once again in the place Solnit wishes we were not.

What’s the problem, here?

For starters, though Solnit feigns taking responsibility, which she does not allude to not at all, and certainly not on Žižek’s terms, we are left moving far afield from the critical questions – How do we imagine individual freedom? And how do we imagine the common good? – and back into a political tug of war.

The irony – or the joke – is that this is how Solnit sees us moving towards a sustainable, compassionate, perhaps egalitarian and healthy and certainly more balanced world. Somehow generosity and kindness and style will begin to take us there. Perhaps. Yet, I see Solnit’s call as Žižek does: an unsustainable attempt to move towards the measure of balance because, as Žižek argues, the very measure of what is extreme has changed. So for me this is the true revolution. It is that totality changed; the very measure of the extremes changed. For Solnit extremes are not going away, so we have to learn how to negotiate with each other – generosity and kindness and style. The world we have will remain.

Will we then have a world within a world? One generous, kind and stylish, moving a particular agenda, the other unkind, boorish and vicious, moving their agenda crudely.

It is here, in Žižek’s thinking, that we are closest to what Solnit is trying to get at when she admonishes – well – the admonishments she, and others on the political left, receive when privileging a good while the same person – Obama = Obamacare + drones – is also responsible for a bad, or even evil, as in the killing of innocent children while also protecting others.

Does the common good, always already arrive to us with good and evil? Is this how we achieve stability, today, or how we define it? Is this who we are?

Historically, we live in a time that, when we talk about stability, says Žižek, it means the stability of dynamic development. It is totally a different logic of stability from that of pre-modern times.

Listen: stability is the stability of instability. Say it again.

The lesson of politics, says Žižek, is that you cannot distinguish between means and ends (goals).This is how we land on Solnit’s notions of idealism, which, she says, is the pernicious idealism that wants the world to be perfect and is disgruntled that it isn’t – and that it never will be. Solnit is closest to Žižek when he describes the source of totalitarian: The greatest mass murders and holocausts have always been perpetrated in the name of man as harmonious being, of a New Man without antagonistic tension (The Sublime Object of Ideology).

Think la Reconquista and the expulsion of the Moors and and the Fall of Granada in 1492 – begin there. Then in the same year, Columbus, instead of reaching Japan as he had intended, discovers a New World. And work your way through history and note how the ideology of a New Man without antagonistic tension wanders through as a harmonious being in a wave of mass murders and holocausts.

The only way this can happen, always, over and over, is if the first condition of ideology is met: individuals partaking in it are not aware of its proper logic, says Žižek. If we come to ‘know too much,’ to pierce the true functioning of social reality, this reality would dissolve itself.

This is why the emperor never has any clothes, as Solnit posits. He is always already naked – only we don’t know it.

It’s best to go further and bring it to a close listening to Žižek, fully:

This is probably the fundamental dimension of ‘ideology’: ideology is not simply a ‘false consciousness’, an illusory representation of reality, it is rather this reality itself which is already to be conceived as ‘ideological’ – ‘ideological’ is a social reality whose very existence implies the non-knowledge of its participants as to its essence – that is, the social effectivity, the very reproduction of which implies that the individuals ‘do not know what they are doing’. ‘Ideological is not the ‘false consciousness’ of a (social) being but this being itself in so far as it is supported by ‘false consciousness’. Thus we have finally reached the dimension of the symptom, because one of its possible definitions would also be ‘a formation whose very consistency implies a certain non-knowledge on the part of the subject’: the subject can ‘enjoy his symptom’ only in so far as its logic escapes him – the measure of the success of its interpretation is precisely its dissolution.

And here we are, inside this ‘ideological bubble’:

- Solnit points to the non-knowledge of the left

- Generally speaking, in Solnit’s words, none of us know what we are doing – not the left, not the right, not anyone

- Yet we are involved in doing, what Solnit suggests is the making of the world

- This is the false consciousness supporting us, what we are doing without knowing, always

- We are, in the West, especially in the US, most of us, involved in the greatest perversity of all: we are enjoying ourselves, even as murderers and holocausts abound

The solutions are, perhaps beginning with Solnit, as here, but then moving to the more critical: How do we imagine individual freedom? And how do we imagine the common good? And doing so with responsibility. It’s the only way out of the bind of trying to create a balance among contrasts, a shallow exercise that leads us back into the bind we’re in. It’s not about victories, as Solnit says; it’s about knowing and understanding where difference are – and they’re always a moving target.

My Final Post on Getting Lost: Lost in the Funhouse…

Our students thrash about because we do; students are terribly confused because we are; we are all a danger to ourselves. And, as far as I am concerned – in one humble opinion – we dutifully adhere to the most medieval institution, the University, without realizing that, before our eyes, it has metamorphosed into an exotic multinational business like any other – and students are our last concern.

The Secret in the Mirror: From section 2 of Imagining Amsterdam

The beginning of Imagining Amsterdam can be found here. Below is what follows, the second section, which I’ve titled, for this exercise, “The Secret in the Mirror,” to comply with our work/play/reading of Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost.

For Hannah and Leah, who brought this story to me. And for Karen who has always been there, caring and interested and thoughtful.

*******************

Some ideas are new, but most are only recognition of what has been there all along, the mystery in the middle of the room, the secret in the mirror.

Rebecca Solnnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost (2005)

In a story such as this, the full view is necessary. Otherwise it won’t work. I don’t want false impressions.

I’ll start with a wide angle shot and push in so you’ll experience what I did when I finally got to Amsterdam in mid May, after I called him, and the city came to me. As he did. Slow like. An animal crouched low. And they rose up. First this city that proved everyone wrong, which is what he used to say – and he not far behind. They arrived together.

— It’s an experiment, like all manmade things in this world. But it’ll be how we’ll all end up, he told me once. You’ll see. That’s why I visit. That’s why I go back. Amsterdam is an answer I like.

I wasn’t sure what he meant. He was off to Amsterdam for spring break when he first told me how he felt about the city. I was a junior. We were always so focused on me – my needs of the day, my problems, my challenges, my dreams and ambitions. Me. Me. Me. The price – or is it cost? – for being young, ambitious and quite privileged, even if I’m not from this country, your America.

I was initially unsure of myself when he told me something personal. It was kind of a shock and I’d nod and grin. That’s all. Not knowing what else to say. I couldn’t continue and keep the conversation going – he knew more, on just about everything. That’s how I saw us. Right or wrong. That’s how it was. But that’s not how I sense us now – then it was intimidating, yes, somewhat, and I was hesitant. On the contrary, though, he gave me no reason to be intimated. Honestly. He gave me lots of space to ruminate, to try things out, to speak my mind. He never judged – and only sometimes laughed – but lovingly that is. He laughed not in judgment, rather something like adorable. His laugh said, Oh you’re so adorable. It’s as intimate as he could be. And he was always encouraging. Always. He encouraged me to take chances with my ideas – with myself. I felt him to be a kind of safety net. He would catch me. I was certain of that. It was never said but I always knew his hands were cupped beneath me, holding me up, watching, alert.

I was always looking up at him. Can you see us? Me, I mean? This is how it looked – how I looked, he and I: I’m slouched in his black rocker, incessantly chewing gum, my legs crossed beneath me, doodling in my notebook opened before both of us on his wide mahogany desk. On the other side, there he’d sit over me, a balding figure, solid, wide-shoulders, fidgeting in his chair, sometimes sitting on one of his big legs that suggested he may have an athlete at some point; he’d lean forward, too, and unconsciously, I imagined, fix his glasses and rub his wide forehead and thick nose, looking out the window – not at me. Tuck his shirt into his rounding belt, into his jeans.

I’d ask: So you don’t like this word, is that what you’re telling me? And I’d point to it, underline it or circle it and turn the notebook or the paper – whatever I was working with at the time – around to him. He’d peer over his glasses, maybe draw it closer to him, slightly – touch the paper I touched (sometimes, rarely, we brushed up against each other) – purse his lips, consider and, more often than not, say, Find something better.

You want me to change it then? I’d ask insecurely, grabbing a different colored pen to make the change (I obsessively applied different colors to different editorial remarks).

Dazzle me. Decide. You’re much cooler – much cooler then that word, he’d say. Don’t settle. You know what to do. You don’t need me. You don’t need me at all. You know best. But never, ever settle. Not if you want to work with me. Not if you want to be a writer.

At first I thought he was aloof, that he wanted to be somewhere else and I was a bother, a spoiled brat that needed to be told what to do – then I learned it was intimacy. His way. The only way for him. He drew me in with compliments that compelled me to reach for whatever it was he saw in me.

It was the well placed sentiment about this and that that began to take hold. You’re much cooler. You don’t need me. You’re much cooler than that.

I thought I was a nerd; he thought I was cool.

You’re beautiful. Really. In all manner of ways.

I would never use beautiful to describe my average self; he thought I was – and it got me thinking, wondering. I lingered a bit longer in front of the mirror and studied myself: straight nose, angular, thick eyebrows, square jaw, full lips and high check bones, black eyes, long hair past my shoulders, thick and black, too, and sort of kinky sometimes (depending on the weather), as is the hair of girls from my part of the world. Tan skin, a dark olive, something not appreciated at one time by Indians, in my country, obsessed with lighter skin tones. But beautiful? I don’t know. Maybe. In college I was exotic – we all were from my neck of the woods – American boys always wanting to get close, touch, see if the mysteries that live in time are true, the Kama Sutra and tales of love; then along the way, gradually, slowly, we became desirable and fashionable – the Archie Punjabi’s of our time – something beyond the ways of kissing, embracing and biting, something closer to who we’ve always been, us from this world so foreign to westerners – a people deeply concerned with virtuous and gracious living and the nature of love, family and the pleasure of human life. In all this he gave me confidence. AndI relaxed. I relaxed into him, like settling into an old, comfortable couch. (Maybe I was settling into my history – I don’t know, the sutra, maybe, and I was returning to this long thread.) I let him see more of me. But it all happened unconsciously. I just went with it, this feeling, a need I felt that called to him.

Was he calling me too? Was he seeking me out? Want me as I wanted him, I wonder now? Or was it that he wanted something else and I didn’t understand? He kept a wide berth between us. But something else happened emotionally.

It’s strange how trust and intimacy seem to reside together, co-mingle. And how strange it is that trust and intimacy begin to take shape – even begin to take hold – before they’re even noticed and then one day you wake up and you’re in this sort of warm, enveloping place, an embrace, something that takes you in. It’s okay, it says. It’s okay. You’ll be alright. So you stay awhile in this new place. You stay and in staying you begin to look for that embrace, anticipate it, even long for the embrace, that secure feeling, that sense that there is a world, indeed strange and foreboding, but in that trusting, intimate embrace there is no other world but you – and yours. Strange how that happens.

No one had ever spoken to me like he did. Not a man, anyway, that didn’t seem to want anything from me – like an erotic T position or something. A man – it’s an easy thing to say, very difficult to understand. A man. I guess when I was in college – when we’re all that age we’re trying to find the measure of a person, making all sorts of foolish mistakes, not really knowing how to be a girlfriend, something like that, and girls like me, we were like always trying to find the measure of a man. Find out what that is. What is a man, anyway? We were raised that way – although in my case “the arranged marriage” was still something of a cloud that hung over some of us, not so much me, because my Punjabi parents are most liberal, which has always been good. Liberal and wealthy, I admit. A winning combination. But whether culturally – or still, because of my culture, man, the man you would eventually have to end up with carries some weight, even some anxiety. So when he said to me, You’re beautiful. Really. In all manner of ways. When that comes at you, it’s easy to be seduced if you’re young and naïve (I can’t say innocent). That’s why I went to him, why I went to Amsterdam. To see. To see if I was a victim of a profound and sophisticated seduction. To see if I was simply some thing he needed at the time – or did he feel differently? But I can’t lie. I also wondered about what it was that I felt from him after all these years? Time seemed not to have worn the feeling away – whatever it was; it seemed to have made my connection to him – our connection – more profound.

Was he someone I used – or was it something else?

Or did I seduce him? Ah…Ah… Yes. Was that possible – and I not know it? Maybe I did know it and I really liked what I was doing.

When I was in school, I began to anticipate and look forward to his well placed personal reflection. You can do what you want. You have it all. Maybe that’s what made things easy between us. I believed him. Maybe that’s trust. Or maybe I was lying to myself and it’s simply the development of an obsession since I remember waking up in the morning and thinking about what he’d said, thinking about him. Maybe he was lying. I went to Amsterdam to find out.

That’s why I need to go slow with you, and push in carefully so that you can take everything in as I did – and see what you see. You decide. You decide, my friend, what you see. Accept what you want. But, I’ll be honest: it’s complicated. People are complicated. We’re all complicated, I guess, liable to do anything.

Let’s start here: I’d never been to Amsterdam. The city escaped me, though I’ve been everywhere else – Paris, Barcelona, Rome, Berlin, Prague. Johannesburg. Delhi (I was born in Delhi). Costa Rica a few times. I don’t know why I never went to Amsterdam, not after it meant so much to him. You’d think I would have wanted to try and at least experience something as he did. You would think. Right? But I avoided it instead. How strange. Freud would say that I was repressing something. Something a long time coming.

PUSH IN: Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, Luchthaven Schiphol, literally Ship Grave: before 1852, the Haarlemmermeer polder – land reclaimed from water, Harlem’s lake – was a large lake that claimed many ships.

Only the Dutch could have sculpted humanity out of an inhospitable landscape. It all started with a simple bridge over the Amstel somewhere in 1275. And here I landed almost seven hundred and fifty years later, alone and apprehensive, nervous, looking bug-eyed at dancing hologram ads and store windows flashing personalized views of me as I walked through the terminal – Urvashi, Bathing Suits! Urvashi, Running Shoes! Distinguished First Editions Delivered to YOU Anywhere, Urvashi!

I turned off my bar code and the ads dissolved, cascading away into thin air, leaving not a trace.

My suitcase quietly floated to me. I only brought one, and a backpack. I felt like a kid, again, a kid in college. I set them down in the crowd. And as I did, as I was letting the bags down so that I could get my bearings, a sinister smile came over me, instantly. He was there. I knew it. He was there observing me. I could feel him. My insidious smile was to let him know, let him into the moment that I realized he was there, with me, again. I wanted him to know. I was playing along. I was here to play. That’s what my half-sinister smile said. A chill ran up my spine.

He stood like a sailor on a ship in rough seas, legs apart, leaning over his arms folded over his wide chest. He’s a big man. A tender grin, like he’d finally found something he lost. Hair nearly all white, longer then I remembered, thinner. A day old light beard – nearly all white too. Blue jeans, a black t-shirt and flip flops, there he was eight years from the memories.

I couldn’t move. My insidious smile fell from my face. I felt something very large and familiar, something that hadn’t gone away but had instead laid dormant, resting in the pit of my stomach, waiting for the right moment to rise.

He didn’t take his hazel eyes off of me. I couldn’t look away either. He approached me and I could sense a freshness I thought came from somewhere heavenly and wild. He had tears in his eyes.

— Again, he said. You’re blushing, he said.

— Again, I said, and smiled. Yes. Again, I said and leaned up to him and kissed him on the cheek, ever so respectfully. I’m just nervous, I said. I’m happy to finally see you.

I raised my shoulders as if to say I don’t know and slid my hands into my jeans’ pockets and bit my lower lip. I think my manner hurt him. He took a step back from my feeble attempt to hide my emotions by appearing somewhat indifferent, casual.

— How’s it going to be? he asked.

— What do you mean?

— This. How’s it going to be? This. Yes.

I don’t know why I became the obstinate school girl at that precise moment – maybe it was because I was scared of what this meant? And maybe it was because I sensed he didn’t know either? And perhaps it’s all I knew to be with him.

— I … I don’t … I’m not sure what you mean.

— Look at me, Urvashi. Let me see you.

I looked up at him.

He reached for my chin and held it.

— You’ve cut your hair, he said. I like it a lot. You look great. You’re even more beautiful. He ran his fingers through my hair and around my face, softly, and said, It’s okay. It’s going to be okay. I understand he said, and he put his arms around me and drew me in and I buried my head in his chest and wept. He stroked my head and kissed my forehead, like he used to do.

— It’s going to be okay, he said. It’s going to be okay. We’re good. All good, remember? All good now. You’re here with me. You’ll see. Everything is good now. We’ll figure it out. We will. Together.

I kept my head in his chest and released myself and I could feel him squeeze harder at every turn, as if he was taking me in by degrees.

— It’s good to see you, he said. Really good. I’ve missed you.

If I push out now – gradually – you’d see the indifferent crowd at Schiphol build to a mass moving around us, passing by as if we weren’t there. We looked like a small island in a foreboding sea. But I couldn’t have been more alive in that moment when he held me as if he couldn’t let me go.

And if I push out even further – and higher – up to Schiphol’s glass roof, and through it into the indifferent sky, blue and wide, we would be lost in a world of movement. We would be nothing. Almost.

The Anecdote of the Gloves

In the “tangible landscape of memory,” as Rebecca Solnit calls it, on one end is the primal scene of my father’s first instance with disease that keeps repeating itself in my life, and the life of my family; on the other end resides the “unseen bodies” that are at work, like strong winds that can be felt but not seen.

To acknowledge the unknown is part of knowledge, and the unknown is visible as terra incognita but invisible as selection – the map showing agricultural lands and principal cities does not show earthquake faults and aquifers, and vice versa (Solnit 163).

What, then, lies beneath?

My trip from Vermont to New York was common enough. I was on route to see my literary agent and, once more, go over a piece we were wrangling over (we parted ways because of it – so it goes, an unseen fault line). The first stop, as it always is when I visit New York, is my parent’s house in Garden City, L.I.

My father, then 82, was not well; that is to say, after 50 years in a wheelchair, taken there by polio, an acute, viral, infectious disease, now a new form reared its ugly head, post-polio syndrome, which, like the original virus, creates yet more muscular weakness, pain in the muscles – what’s left of them – and fatigue. Post-polio syndrome’s wickedness is that it crashes life’s party some 30 years after the original polio attack. My father’s case. To add to the picture, it had been recently discovered that my father also had leukemia, a type of cancer of the blood or bone marrow – and not unusual given his age and condition.

His immovable frame in bed brought me back to my childhood when he was returned home after spending time in an iron lung when polio first attacked and left him totally paralyzed. I stood at the edge of what then, for a 6 year old kid, seemed like a giant, cold, green cage with levers and pulleys. I held the metal bars at the foot of the hospital bed and peered through at the face I knew – the new man I didn’t. This was 1960, Córdoba, Argentina – the primal scene that changed everything. Fifty years later, in Garden City – GC, as we call it – he looked tiny, child-like, as if dissolving, though he was once 6 feet tall.

In another life, he and I rode his motorcycle to Villa Carlos Paz, sometimes running out of steam and having to push it up mountainsides. I wouldn’t again mount a motorcycle until I was 19. I didn’t return to Argentina until I was 50.

It’s amazing how age and disease reduce us to almost nothing, churn us into something else – the ill and the healthy together. How we whither, becoming smaller as if somehow Nature understands that’s what we need to pass on. Until eventually we’re nothing – so it appears.

Lucretius, in On the Nature of Things (De rerum natura), says that, “…things cannot/Be born from nothing, nor the same, when born,/To nothing be recalled.” Nature, he says, “ever by unseen bodies works.”

“You have to come with me to the doctor’s office,” said my mother. “I can’t do this alone,” she said.

My father had been through a series of tests that would determine his prognosis. He was hopeful that somehow science – his one touchstone in life (he was a man of science and mathematics) – would know how to bring him back, at least get rid of the leukemia and, though bedridden, enable him to live a bit longer. My father’s appetite for life was voracious.

“There’s nothing more to be done,” said the doctor, someone my father, a very loyal man, knew for 40 years.

“I can’t face your father with these news,” said my mother. “I’m going to ask you to tell him. I’ll be there but I can’t do it. You have to. I can’t. Not after all the life that’s between us.”

Emerging from Penn Station, in New York, I wasn’t sure how I would approach my father with his death sentence. I was lost, literally, in a search for courage. I was totally in the dark. Completely. I wasn’t sure, either, how this was to fit my story – or into a story – since we live by stories; but I was sure that I had to create a story in which the title character is told that he has an expiration date – and it’s near.

Deep in my thoughts – perhaps deep in my soul questioning father and son roles – just up ahead of me, on 31st and heading towards 7th Avenue, an old man in a gray overcoat dropped a black glove. I caught up to the glove, picked it up, and caught up to the man, tapped him on the shoulder and said, “Here, you dropped this.”

“Thank god my wife’s not here. You saved me,” he said, chuckled, thanked me again and we were off . I turned right on 7th Avenue, making my way toward the Flatiron District. My agent was on 22nd.

Not five minutes later, nearing 22nd, a woman trying to speak to her friend while balancing a shopping bag and a handbag, drops a beige pair of gloves. I thought it strange that I’d see the same thing so quickly. What are the odds? I picked up the gloves and faced her and said, “I think these are yours.”

She gave me a beaming smile and said, “Oh. Yes. Oh. Thank you so much.”

And we went our ways.

“Even when deprived of all but all the soul,/Yet will it linger on and cleave to life, –” writes Lucretius.

And, says Solnit, “A story can be a gift like Ariadne’s thread, or the labyrinth, or the labyrinth’s ravening Minotaur; we navigate by stories, but sometimes we only escape by abandoning them.”

That afternoon I abandoned one story, the one my agent wanted me to tell. I wanted to tell it my way, which I did. But what I didn’t know is that I was already in another story – aren’t we always in someone else’s story, after all?

On the return walk to Penn Station, a wind kicked up. It was overcast and chilly. I was thinking that it would be a good idea to slide into a bar and have a stiff one before heading back to GC. When a middle-aged couple comes out of a building and an elegantly dressed woman drops a pair of red leather gloves. The man with her, also quite elegantly dressed, didn’t see them.

The red gloves looked huge to me, bigger than they actually were. On this the third set of gloves dropped before me, I was certain that something unseen, some force was talking to me.

Here’s Lucretius again – he explains it best for me:

And as within our members and whole frame

The energy of mind and power of soul

Is mixed and latent, since create it is

Of bodies small and few, so lurks this fourth,

This essence void of name, composed of small,

And seems the very soul of all the soul,

And holds dominion o’er the body all.

I could find no reason or logic; I could not locate the language by which to describe the first dropped glove, then the second, and now the third that came with a thunderous roar from a place “void of name.”

When I got home I stood by my father’s bed. My mother at his feet.

He looked up at me with his incredible blue eyes, as if pleading yet knowing.

“This is it, viejo,” I said. “This is it. It’s hard to say so I’ll be straight,” I said. And he grinned. “There’s nothing more we can do. Nothing more.”

On the final day of his life, the woman that took care of him came into his room; it was a resplendent day. And she said to him, “It’s such a wonderful day.”

And he said, “For you. For me it’s not going to be a good day.”

When he left us around 10PM, my mother instructed one of her grandchildren to open a window.

Imagining Amsterdam

Transparency: The following is from a novella I’ve written (now editing), Imagining Amsterdam. The story takes place in the future – 2025. I’m publishing the first few pages because it fits Rebecca Sonit’s A Guide to Being Lost – you’ll see why.

*******************

IMAGINING AMSTERDAM

“And in the pursuit of his love the custom of mankind allows him to do many strange things, which philosophy would bitterly censure if they were done from any motive of interest, or wish for office or power.”

Plato, Symposium, c. 385-380

“Why should a set of people have been put in motion, on such a scale and with such an air of being equipped for a profitable journey, only to break down without an accident, to stretch themselves in the wayside dust without a reason?”

Henry James, The Wings of the Dove, 1902

“People look to the future and expect that the forces of the present will unfold in a coherent and predictable way, but any examination of the past reveals that the circuitous routes of change are unimaginably strange.”

Rebecca Solnit, A Guide to Getting Lost, 2005

–If I think back, I’d say that some of our most moving times together were when you thought you were about to leave behind something of yourself, he said over the phone. And … I don’t know, maybe sometimes you couldn’t. I don’t know. Or wouldn’t. You’d hold on. Tight. You’d hold on tight. To everything you could. Until you couldn’t.

I don’t know why I reached out to him after so many years. But I did. And here we were.

— There’s something of that now, I’m guessing, he continued in a soft tone. He paused, and waited.

— I’m sorry, I said, unsure of what else to say in the awkward distance I felt between us when I heard his familiar voice and it all came back to me again. I took too long, I said. I’m sorry, truly. I am. Too much time has passed. I know it has. I let it happen. Not you. Totally irrational, I know that too. It was me. It’s me. My fault. I feel terrible. Do you forgive me?

He chuckled.

— All I have to do is shut my eyes and I see you, he said. I’ve been watching you from afar.

I smiled. Instantaneously.

— You didn’t think I would? he asked rhetorically. You probably knew I would. How could I not? I always wanted to follow you. To run away and follow you.

— And?

— I would have loved to follow you to New York and see what you were up to. Such a change for you, not going home and all. So far away, you know. So far. And you struggled and came through. The complete you.

— You mean the completion of who you thought I was.

— Something like that. The complete you, I like to think. All of you because I knew I didn’t see everything and I wanted to. The real you, you know? All of it, scars and all. I remember your scars. I can see them clearly, the parallel lines on the inside of your leg by your knee. They’re as clear as your name. Like a signature. A scar, a blemish, something that distinguishes a person becomes so much how you experience a person – you and the person. The scar becomes an intimacy, draws you in like. It has a history. Yours and then someone else’s, I think. And at a certain point, in the here and there, in memory’s shadows, you’re not sure whether it’s the scar or the blemish or the person or all of it that you love. The one and the other become one thing in your mind and that unique mark you just can’t do without is suddenly yours too. You even long for it. That scar.

It was night. I held my lights low against the luminescence stitched across the city and my reflection on my picture window talked back to me: head tilted to one side and rocking back-and-forth cradled in his voice, my arms crossed just above my waist as if I held a child. He filled the room. It was like it used to be.

I know he felt my hesitation.

— I wondered about you, I said softly, like a single syllable, a moan. I thought a lot about you. I did. I wanted to reach out – many times. I’d be grocery shopping, you know – I could be anywhere; on a date – and suddenly there you’d be, out of nowhere, something you said to me – in your voice, your tone. Something I’d forgotten. I could totally see you. It’s good when that happens. I don’t know. Just good. Good all over. I’ve always felt like … That you were looking out. There with me, you know. You were there. I liked that. I liked knowing that you were watching out for me. I wish I could really explain what that feels like. I’m not doing a very good job right now.

I went on and again told him that I was sorry for taking so long to see how he was, how he was doing since he’d meant so much to me, all those hours working with me – years actually, from twenty ten to twenty twelve. Advising me, mentoring me, putting up with my pouting, my tears, my wild rants. Holding me up. My self-involved irrationalities. Until one day something happened and we found ourselves somewhere else, a new place, inhabiting new spaces. Or the same places differently. It was near the end, almost to the end of my university life, the last year. We were in a very different space. I didn’t say a thing though, totally unsure of myself. Either did he – he knew better. He could see the long now and took care of me.

–What happens? What happens to people? I asked him, wanting to really ask him, what happened to us? since there was a time when I spoke to him almost every day just about. Emails, texts, voice – Can I see you? I use to say. I never asked about him. Never. Hi, when can I come and see you? That was enough. That was it.

— You have a life. Mine is quite different. That’s all. We’ve always been separated by a swath of time.

I’d forgotten what it was like, his ability to see through me, instantly.

I was staring into my tarnished memory of us, looking for answers, looking to see why him, why is he still here, here with me?

— You know, I’d say that we met because there is such a difference in our ages. Maybe without that difference, who knows, maybe we wouldn’t have met, he said.

— But we did and here we are …

— Again.

— Again. Here we are again, I said and my voice trailed off and I changed the subject. I wasn’t ready to get into an examination of our relationship, especially since so much time had passed. I turned it over in my mind many times – and maybe that’s why I never reached out. I didn’t want to get to the questions. Yet here we were. As he said, again – a musical phrase that never goes away.

— Boston said you’re on an extended leave. What are you doing? Are you gone for good?

He took a deep breath that filled the silence.

— I’ve stepped away from the hallowed ivy – and come to realize that the ivy has tentacles that reach far inside a person. It’s ironic. And maybe tragic. A little tragic, anyway. That’s what I’m here to find out. I’m taking a step back to find out who I am once and for all.

— What are you saying?

— Just getting some distance. That’s all. Trying to gain some, you know. I need perspective. I’m trying to get it somehow – before I become more irrelevant then I already am.

— In Amsterdam. Talking about some change. Okay. Fine. But I wouldn’t call you irrelevant.

— We won’t be able to meet for lunch. That’s true. Yeah. You can’t simply walk across campus to my office, shut the door and spend a few hours. Impossible this time around, he said and laughed.

— That’s not what I’m saying. Is that how you saw it? A cliché, that’s what it was? You? What am I then?

— It’s a joke. I’m just joking. Common on. Can’t you take a joke after all this time?

— It’s not a joking thing.

— Well then, maybe I am a cliché – and it is too late. Maybe that’s the joke – and it’s on me. Wait. Wait a minute, he said and paused. I – am – being – tested. Aren’t I? Yes. You’re testing me. I think yes. Is that why you called? Wanna see if I’m still here for you. Talk about clichés. That’s why you called. You’re not sure where we are. Me. Where I am. Must be serious. And there’s a change – something’s coming. Some change. Something’s in the air and you reached out. That’s it. It is. Isn’t it? Maybe something already happened. Something big. Love shattered? A disappointment. There’s been a disappointment, yes – and you can’t write it off as all good, like you used to say. It’s got to be big. Yes, something’s happened. What? Tell me. What do you need? This is how it always goes for us, right? Doesn’t it?

— Okay. Okay. It’s on me. I know. It’s on me. I’ll take the chance. I’ll leap. That’s what you want. I hear you. I’ll take responsibility. But you can’t say you’re a cliché. I won’t accept that. You’re not a cliché. You’re not. Far from it. Don’t be ridiculous. You mean a lot to me – to a lot of people, I said to him.

Then I hesitated, unsure whether to say what I wanted to say, why I called him, after all. There was a long silence – and I just said it: I need you. As soon as I said it I regretted it but I kept on. I was already in. I was in the moment I got his number from Boston. I was in when I called him. Shit, I’d been in for awhile.

I breathed deeply a couple of times, and nervously just put it out there quickly: Are you busy? Can I see you? I asked and dropped my head, letting its weight dangle it there over my chest as if I’d given out. I shut my eyes and waited. I waited for the cold, sharp blade to drop on my neck.

My anxiety thickened – and he let it.

— Are you ignoring me?

He didn’t respond. I inhaled, not wanting to look up, even though we weren’t visible to each other – I shut off the broadcast just as I called him and I leaned on my picture window, full of anxiety, and whispered facetime off because I didn’t want him to see me like that. He’d sense my despair. That’s what he’s really good at sniffing out. Despair. We met at precisely the moment I was falling and spinning out between reason and chaos – and I didn’t know which was which. I sat hunched over in his seminar on punishment, my thick, black uncombed hair around my face covering my eyes. I was disconsolate. Didn’t know where I was and what I was doing. More importantly, I didn’t know what I was going to do with myself – and I didn’t know who to turn to. You might say that this is expected of any second year university student, particularly if she is surrounded by classic “A” personality types with their lives totally visible in front of them. Mine was not. I was lost. I can’t even tell you why I took his class – maybe it was the rumor mill we students create and someone told me, oh yeah, take him, he’s interesting. And I did, not knowing what else to take. I just didn’t care. I hardly looked at him when he lectured. And he pointed to me one day at the end of class and said, softly, simply, See me. Just like that. See me. That was that. It began then, the spring of my sophomore year. See me. I saw him alright.

I circled my Tribeca studio.

— Are you busy? I asked again. Can I see you? What else do you want me to say? Can I see you? That’s what I want. I want to see you.

A hard rain began knocking against my window.

— Why are you not responding? Why are you doing this? I need to see you. Okay? I need to. I need … What more do you want? You know my history. Why are you doing this? I can’t make it up to you, all of it. All this time. Okay? What else can I say? I can’t – but I want to see you still. I’ve never known you to be cruel like this. What?

— No. Don’t do that. It’s not what you’re thinking. Please, he said, jumping in almost out of breath. I’m sorry, he said. I’m not testing you. I would never do that. You know that. I don’t want anything from you. I’m sorry. It’s just that when you asked me whether I was busy you put me instantly back in my office and there you were standing in my doorway – sweating, out of breath, smiling, like when you went for runs, your hair in a pony tail over your left shoulder and you’d stroke it and fix it compulsively. You asked me whether I was busy and could we talk. That’s all. That’s all it was. I was there. Inside that. It just came over me like that, all of a sudden. I was lost in it. And I hesitated. I’m sorry. There was nothing I could do. I hadn’t thought about anything like that in years – and it took me. Completely. I’m sorry.

— What do you think?

— I think that it may go like this. Things fluttering back and forth and that we have no words for. We’ll have to adjust, I guess. That’s all.

I saw him reclining in his leather chair, his feet on a large oak desk, Walter Pater or Henry James opened on his lap. He was graying, rounding. And he’d give me a big smile, sit up and nod to the black rocker, a crimson H engraved on the top rail, in front of his desk and say shut the door.

When the curtain came down on my Boston days and side-by-side with sixteen hundred undergrads walked into the wide, foreboding world we all feared – reality we called it in the sanctity of our luxurious schoolyard – I knew I’d had something special, something different that nobody else had experienced. His careful eye on me.

Maybe that’s why I called him again, to learn what it was that I felt, why I couldn’t shed it after all this time, that feeling that something happened to me. Maybe I wanted it again. I missed the light tap on the shoulder, a constancy that one day appeared, and stayed. Until I learned to predict it. Until I learned to see myself as he saw me. Until I could no longer feel obstacles between us, no challenges – only a genuine sense of freedom. Freedom. Just freedom. I longed for that feeling, the ease, the smoothness to be. I didn’t have it when I called. I’d lost it somehow – at some point.

— It would be easier if I saw you, I said. I think, anyway, it would be easier. I want to see you.

— Come. Come then.

I thought that seeing him would be simpler – a ride up to Boston. But nothing about us was simple, ever. Addicts of complexity, that’s what we seemed to be. I am, anyway, I think.

— Come, he repeated. Come. See what I’m doing. We’ll talk. See what you’re doing. We’ll talk about writing like we used to. We’ll read something together. Remember that? Take as long as you need, he said. But come.

— To see why it is that after all this time – how long has it been?

— Eight. Eight or ten years, something like that.

— Why now, after eight years – let’s say that – I call, and want to see you?

— That’ll be part of it, I’m sure. If you want. Sure. It’s something. Something is there, yes.

— And why, after all this time, it’s you I’m looking for? Again.

— My sentiments exactly. I can tell you that. So come. Stay. Let’s see. Come before it’s too late.

Ever since, I’ve not stopped imagining Amsterdam.

*********************

Home Grown Quasi Reconciliation

Meno, Socrates’ fresh victim in Plato’s “Meno”, is (as Solnit rightly points out) Royally kerfuffled by our Master of Reasoning. But not entirely before he, Meno, utters his infamous paradox, which Solnit uses to introduce her theme in Chapter One.

Oddly, she doesn’t acknowledge that this initial (and, one presumes, central) quotation is a paradox. “How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?” This genuinely is unanswerable.

Perhaps Solnit is deliberately kissing reason goodbye, because Chapter Two–the first of the Blue Distance chapters–is full blown impressionism; her apparent native dimension and tongue.

I think that impressionistic prose is at its best as a sort of sub genre to poetry. Like poetry, it requires the author to sort of be willing to abandon both reason and [literary and societal] tradition (even if these are returned to). It gives pleasure in and with its loveliness (even very dark loveliness), and passages of this chapter are truly lovely.* Impressionistic prose flies nowhere near as high as poetry, though.

It seems I’m going to write stuff here chapter by chapter. Sorry.

*Helene Cixous and other European feminists I can’t remember by name use impressionism as a weapon, but that’s another story.

Home Grown Spasm of Skepticism?

Now I am the proud owner of not one but two copies of Solnit’s Field Guide to Getting Lost, both straggling in from Amazon through a flurry of snow yesterday. (One copy easily accessed in it’s good old brown manila envelope; the other in one of those white, deceptively flimsy envelopes you first try to open with your incisors; then with your molars; then with a chain saw).

(I will give one copy to my friend ,Tom, who has always been hair-raisingly open to gifts and other things from that Solnitzian door into the dark .(p. 4) Perhaps he will want to ask Hector if it’s ok for him (Tom) to join us.)

So, Field Guide. I know that as a reader I am annoying to some simultaneous other readers of any given text. I generally read slowly and bear down on every word (thank you, H. James), extracting the savor of each sentence while keeping in mind the bigger picture/s the prose develops. Readers who go right for the big picture—and usually also the larger strokes that make it up, can feel reined in by my gait.

For example. On only page 5 of her Field Guide, Solnit quasi-rhetorically asks: “How do you go about finding these things that are in some ways [?] about extending the boundaries of self into unknown territory, about becoming someone else?” WHOA! This is big. It begs many questions indeed. Such as (but only most obviously) am I someone else than I am at this moment here if instead I’m in Siberia, and then again another self out of a cloud of empiricism in Saks Fifth Avenue? Actually, the question’s not ridiculous given her sentence as it stands.

I call sentences such as Solnit’s quoted one “provocations.” They themselves are ambiguities causing our reader brains to do some of its own work before the author’s commencing to unpack them (the unruly sentences) in the writer’s own terms which we’re reading for, thus to our edification. The fair play assumption that the author will do this.

You know how if you’re riding your horse, and it’s proceeding at the stipulated canter, head center, and it momentarily cants its head slightly askew, and you know it’s just gotten new ideas about what we’re going to do? Well, right after Solnit asks (I repeat) “How do you go about finding these things that are in some ways about extending the boundaries of self into unknown territory, about becoming someone else?” she cants askew and gallops from this to Oppenheimer and to Poe. No carrot at the barn for you, Rebecca!

Harsh? Of course. It’s a book, for crying out loud.

I am on page 10. Where are you others? Shall I put things aside and wrap this up in order to carry on with y’all?

Karen

Home Grown Species of Lost

Hector Vila invited me to join this exploration of “A Field Guide to Getting Lost.” I ordered the book from Amazon and never received it because it got lost. I have reordered, but meanwhile I’ve been thinking, and I have especially recalled one of five occasions of getting lost in my life. So I will include it, albeit it not Kosher to do so. Maybe I’ll find a chapter to match it? This particular incident, as I will soon say, tore all my familiar sense of my Self out of me. So I submit it as an experience of being really lost. Thus:

My phone rings in funky harmony with the dryer’s buzzer going off. This sends a micro-wisp of pleasure through my mind.

On the phone is my daughter Kia, sounding cheerful: ”Hey, Ma, how you doin’?” Too cheerful. Exponentially too. So then I find out she’s sitting next to my younger son Karl, who is unconscious, in an ambulance headed for Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York city. Karl is unconscious. Karl has had a stroke: he is unconscious. Prognosis, as they uselessly say, unknown. Karl has had a stroke; forty years old. Unconscious in the ambulance to Columbia Pres.

My daughter abandons the Cheer-to-Protect-My-Mom and sobs extremely hard.

My elder son Yani has been dispatched to pick me up, and together we’ll.

I wait for Yani out in the driveway, which I am I am tacking around like a Roomba. All that has been Me in all domains of my Self’s being has fled out of my husk. (Only but my autonomic nervous system seems to be hanging in there because my heart.)

I glom onto the fact that here is one preternatural particular pebble in the driveway gravel. It’s about the size of a chickpea and has a greenish tinge. One half is smooth and ovoid; the other half sharply fractured away. All this waiting time he may be dead. I’m looking keenly at that pebble when Yani drives up.

The very many many cars on the West Side Highway are all driving to unique particular somewheres. I spit on all those lives in our way. Plus which also: What is happening now inside my daughter and son here? I must: I have to. This is a time of how to do anything now.

That night everyone gone home but he and I. ”Not out of the woods yet” they say. Almost all night I very very gently hold his bare hand. Forty or not, his Mom holds it.

Nurses never come in to see Karl. They’re off in their monitor room watching critical monitors instead.

I stop one other nurse in the hall and PULL her: ”You’d better come and see my boy. See him. Please. He’s not your fucking blips.”

She waits till I stop crying and she brings me a useless cup of tea.

There isn’t one thing I can do all the night so I very gently hold his clay heavy hand.

There is no way anymore for me to be his mother who helps him; to demand help for him; for anyone to help me help him.

The word “miraculous” was hurled around the hospital a lot, and we all loved it. There was lots of shaky joy. It took awhile afterwards for everyone to be OK. Of course it took Karl longer. They told us he has a hole in his dear heart the size of a pinprick; that 30% of all people have this wee hole but most never know. That people who have such a stroke as Karl had are then really disabled, or else they die.

So I ask Karl, four years after his stroke, how he feels. He tells me that when he plays the bass in any of his bands, his left pinky feels a little stiff. I tell him to suck it up.

Abandon

She places her chin on my desk. She leans over, arms on her thighs and rests her chin on my desk.

— Professor, I don’t know. I … I don’t feel anything. I … I’m indifferent. I don’t feel anything. I don’t. I just don’t feel anything.

She walks into my office with a big smile. She wares a white wool turtleneck and her silky black hair, parted off-center on her left, falls around her face and over her shoulders like a frame calling attention to her lively eyes – and her smile.

— I miss being here, she says when she walks in. It’s a free place, she says and sits in a chair opposite my desk.

Then nodding to the Green Mountains always in my office window, she says, There are the mountains that will be here when you’re not. And giggles because she’s referring to an email she sent earlier wondering what would happen if one day she came to my office and I’m no longer there – after all, I’m an “old professor,” as she likes to remind me.

–I’m like the mountains, I said to her once. I’m always here, I said trying to convince her that I’d be here for her when she needed me.

She knows better. I’m not like the mountains. One day I won’t be around anymore. So how far does one go knowing that a relationship is terminal?

For her, it takes time to go from the self-restrained person that first walks into my office to the person with her chin on my desk confessing that she’s indifferent. Layers have to be peeled before going there. It will take some time for me to learn of her sense of indifference; it will take time for her to let it out.

That’s why I keep a box of Kleenex on my desk.

–I’m never going to use those, she says looking askance at the box. No. Never, shaking her head – No – and grinning and two small creases, like commas, on either side of her lips appear and turn up.

We’d been through a lesson on Vietnamese. She told me that she never curses in Vietnamese – and doesn’t say I love you. It’s because, unlike English, Vietnamese is physical, I’m told. Words appear more significant to her in Vietnamese; she feels them. She curses in English because she’s not physically connected to the language; she can throw around love and my friend this and my friend that just as any American does. Not in Vietnamese. In Vietnamese she’s been taught how to speak properly, especially since she’s a young woman. Certain things are just not said in Vietnamese, she tells me.

I ask her to teach me a curse in Vietnamese. She can’t. Won’t. I plead. Insist. No way. Can’t. Impossible. Can’t go there.

Instead she reaches for her phone and scrolls and reads me a poem, Đây thôn Vĩ Dạ, by Hàn Mặc Tử’, a famous Vietnamese poet that tragically died much too young, stricken by leprosy.

–Here’s what Vietnamese is like, she says, and reads. When she ends, she leans back in her chair and smiles at me, darts her eyes. It’s beautiful, she says. And explains the poem in a sentence or two – as if she’s applying a fine scalpel.

Vietnamese is soft, gentle. I can see how it comes from the body; her physical presence changes. It fills and speaks.

Then we listen – and watch – a Vietnamese woman recite the poem on YouTube.

–It will sound different, she tells me. It’s in the dialect of the poet. It’s different from mine.

I never knew this, the varieties of Vietnamese. Why would I? Vietnam has always been one dimensional for me.

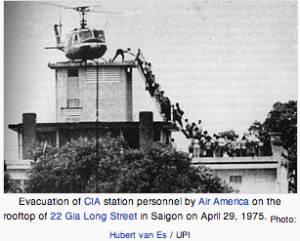

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident (1964), My Lai (1968), Nixon and Cambodia (1969) – and my registration for the draft. The fall of Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), the capital city of South Vietnam, April 1975. Apocalypse Now (1979) – and consequently, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. Oliver North – Platoon (1986), Born on the Fourth of July (1989), Heaven and Earth (1993). And The Quiet American (2002), with the incredible Do Thi Hai Yen playing Phuong.

–Did you read the book? I ask. It’s by Graham Greene.

–No, she says. Then in a kind of excitement, as if discovering something, Everyone wants to possess Phuong, she says. She’s so beautiful. She’s everyone’s fantasy. Each man’s.

–A nation’s, I say.

Vietnam was an American fantasy – as it was a French one. And this young, sensitive student, for this “old professor,” is two Vietnams: the one she didn’t know but sensed as she was raised in a post-war Vietnam; the other is new, vibrant, slouching towards modernity.

Ruins become the unconscious of a city, its memory, unknown, darkness, lost lands, and in this truly bring it to life. With ruins a city springs free of its plans into something as intricate as life, something that can be explored but perhaps not mapped.

This one young woman sitting in my office is a Vietnam, I realize, that, as Rebecca Solnit says in her “Abandon” chapter, cannot not be mapped (A Field Guide to Getting Lost); her eyes, her smile, her wit – all invite exploration. She is tomorrow, not today. In her somehow are the ruins – what has given way since 1975 and re-surfaced in new formations in her sophisticated ways of examining my office, her world, the life she’s had, even though she’s so young, but 19. She seems older, traveled beyond her years. She dissolves into something more remote then now, past it; she points to something yet out of reach for us, something she’ll see and live. And I will not because I’m not like the Green Mountains outside my window.

“Beauty is often spoken of as though it only stirs lust or admiration,” says Solnit, “but the most beautiful people are so in a way that makes them look like destiny or fate or meaning, the heroes of a remarkable story.”

This is who she is, this young woman – beautiful like this. Fate and meaning. Something remarkable she yet quite doesn’t understand and is terribly frightening. We’re invested in the plight of humanity and “exceptional beauty and charm,” as is hers, “are among those gifts given by the sinister fairy at the christening,” says Solnit. Humor and irony – and darkness. The child, at christening, never knows and spends the rest of her life trying to know – sometimes in fear.

–I don’t want you to think, professor, that I’m like this person who writes constantly. I don’t. I don’t even like writing, she informs me. I don’t feel anything, professor. Nothing like that.

This is the same person that, early on, told me that she loves language; she loves looking up words in the OED (Oxford English Dictionary); she loves rich, figurative uses of language. The same person that keeps beautiful poems in her phone.

This is the same person that, in a piece titled The Necessity of a Heart, writes:

Now and then I saw my mother’s gleaming dark brown eyes fading. Her eye color is that of tamarind candies and papaya seeds. I soon learned that tears could wash away one’s eye color the way they did my mother’s. So I never cried for long. I loved my eye color – the color of tamarind candies and papaya seeds.

This is a story of the various ways my eyes change color.

This is the same girl that feels indifferent – yet feels deeply, in a way that is beyond her yet. This is the same girl that has a ruthless imagination that she unleashes routinely in phrases that reach for the heart, always.

Adventures enthralled every piece of me. At ten years old I read the story of Helen Keller whose saying I remember by heart ever since: “Life is either a daring adventure or nothing.” At twelve years old I was determined that I would either grow up to be a reckless adventurer or I was already dead at birth.

I remind her of this other girl that visits my office and I suggest to her that her talents are way out ahead of her maturity – for now. I tell her that she’s not indifferent – the opposite: she feels deeply and emphatically and can then turn these complex feelings into images we can recognize as our own.

–I’m not used to this, professor, she says. No teacher has ever spoken to me like this, she says.

Her shoulders have relaxed. She’s played with her beautiful hair a few times and now she’s parted it from right to left, the opposite of how she had it so well put together when she entered my office.

–I love my parents, she says. But we never speak of love. We don’t say I love you. And you show me all this unconditional love. I don’ t know what to make of it, she says, welling up and looking over at the Kleenex.

–That’s why they’re there, I say.

–No. Never.

I reach for the Kleenex but she beats me to it.

Que voy a ser, je ne sais pas

Que voy a ser / What will I be Je ne sais pas / I don’t know Que voy a ser / What will I be Je ne sais plus / I don’t know anymore Que voy a ser / What will I be Je suis perdu / I’m lostAfter I learnt the real lyrics, I decided to just go along with my interpretation because by that time, I’d been through a series of moments related to figuring out my identity, my place in this world, these cultures and I held on to these words like a security blanket. It was okay for me to not know who or what I would be, because how could I? After having begun Solnit’s book though, I found myself thinking increasingly about the last line – Je suis perdu. When I think about it as part of the song, there’s no sadness associated with the idea of being lost. The beat, the voice, the melody – they’re in complete contrast to the lyrics. I’d never heard of anyone so cheerful – for lack of a better word – singing about being lost. (Sidenote – it’s stuck with me so much that this bastardized phrase of mine is currently at the top of a very short list of what I’d like to get as my second tattoo.) I talk about the song because I’m halfway through the chapter Abandon and it talks about a musician friend of Solnit’s, her journey and the various stops along the way, some of which may seem like the wanderings of a lost soul, but in reality are very much conscious choices. It’s interesting to try and really pick at the subtle differences between loss and being lost. In the way that they are used in speech and in language, loss almost ends up as something passive, something that happens to you, whereas being lost is an intentional act, a choice to loose certain elements, certain aspects of one’s life. Whether we do it consciously or subconsciously, I think we all discriminate a little bit against certain lifestyles and life choices that imply an intentional loss. I bring up this point to link back to the train of thought Solnit weaves through the latter half of the previous chapter, The Blue of Distance, when she talks about culture and boundaries and the repercussions of natives kidnapping many of the Puritan children and their resultant choices to stay with their captors/new communities. When I read that, i actually dug through my inbox to find an email thread dating back to August 2011 – a fervent online discussion with a few friends about reflections from working in the international development sector, and empathising with The Other, figuring out how to transition back to the world we came from. I think it was there that I first started playing with the imagery of boundaries and fences and imagined/defined borders for spaces that we inhabit, or look to enter, or have invariably found ourselves a part of without even realizing when or from where we entered. The more I think about it, the more I’ve reflected this imagery subconsciously during crucial moments in my life. I went to an international high school for two years, and remember always recollecting that experience in conversation or on paper as both a blessing and a curse – it was almost like i had been broken into a million little pieces during those two years there, and when I stopped to pick up the pieces and reassemble myself, I found that I was no longer myself but an amalgamation of everyone else around me. Pieces of them were deeply embedded in me, and have been ever since, and pieces of myself now live in other people. What did I lose/gain in the process? Can I really say that I’ve been the same person since then? What I didn’t realize is that the process of reassembling yourself and carrying on actually is almost an art. Not to sound presumptuous but many a person has broken down at the idea of losing the sense of comfort, of knowing who you are, what you think, what you want and where you’re going. Solnit rightly says that “the real difficulties, the real arts of survival seem to lie in more subtle realms. There, what’s called for is a kind of resilience of the psyche, a readiness to deal with what comes next.” I found another quote from The Pedagogy of Self, that I began reading when I was thinking about boundaries and fences and this situation of knowing the Other and consequently one’s own self better, that puts a very visual interpretation in front of me of what it is actually like to be that hybrid, that in-between who is crossing cultures, losing and finding oneself multiple times to the extent that loss and discovery are rarely distinguishable from each other….sometimes the presumed sadness of loss actually manifests itself on discovery of oneself or one’s purpose because that is where the journey supposedly ends, doesn’t it? The quote reads:

The hard edges of the boundary between self and other become fuzzy. Where we end and the environment begins becomes a shared space. It is not so much that we become fuzzy as we become aware, through heightened self-awareness, that we already exist in a state of shared being with all of life: It’s less a change in reality than a change in perspectiveI really can’t find a coherent way to end this because, as usual, I get lost in what I’m writing. But I’m leaving pondering about the curious nature of the universe, in making things make sense. With the song, with my tattoo, with these emails from two years ago and everything tying in to Solnit’s treatise on being lost. I guess that’s a commentary in itself, isn’t it? Have we ever lost something, or are we ever lost, or merely just waiting to find again?

Exile on Mainstreet: Lost on the Boundaries

I was an exile before I had time to reason.

I was an exile before I understood the feeling of banishment.

I was an exile before I could gain insight into the morphology of political systems that are always already expelling one’s consciousness.

Exile first arrived, unannounced, quiet like a lion in the bush after his prey, through family – a father out for weeks making napalm, a mother ironing the family clothes with a revolver strapped to her side, a machine gun parked in the front yard, gun fire, deafening rockets overhead, sleepless nights, whispers and apprehensive glances.

To a small boy hiding beneath stairs the powerful surge to push him out and away is not that; it’s more immediate, more frightening, more resolute. Textured hostility. A bully in the schoolyard. The authoritative forces that expel a person from his place are far from one’s life; they are nebulous and foggy and distant from one’s dreams and desires. Which is why exile is so profound.

Exile, says Edward Said, “is a condition of terminal loss.” In the modern age exile has become a “motif of modern culture,” he says. “Even enriching.” Listen: “We have become accustomed to thinking of the modern period itself as spiritually orphaned and alienated, the age of anxiety and estrangement.”

My anxiety and estrangement began in 1960. My family came to the United States, on this first trip, because my father was stricken with poliomyelitis, a virus that left him paralyzed from the neck down. No one could help in backwater Argentina. My father was 31 years old. He passed away at 82. He spent 51 years in a wheelchair – and he was highly accomplished. He spent 50 of those years in the United States – as we did.

Our anxious and estranged, final move to the States came in 1966 – there was no hope in Argentina.(Ten years later, Argentina experienced a Military Dictatorship that lasted until 1983 and a Dirty War, which was part of Operation Condor – there would be nothing left, eventually, and the country has yet to recover.) My father and mother were hedging. History says they were right. Our age, says Said, “with its modern warfare, imperialism, and the quasi-theological ambitions of totalitarianism rulers – is indeed the age of the refugee, the displaced person, mass immigration.” We were just that, my family.

I became intimate with displacement – sensually, instinctively – before I knew of the concept. It happened the day my father was brought home from the hospital, after spending time in an iron lung, and the nearly lifeless man stretched out in a green hospital bed was no one I recognized, not intimately.

In an instant, I lost my home, I lost my country. Displacement is very real, a life-force, an elaborate gild. It leaves a scar – and you leave something behind, too. I was 6 when my father took ill. I was 11, almost 12 when the displacement was complete.

I had to learn how to adjust, how to adapt to survive. I didn’t have a guide – and I was lost, though I can honestly say I didn’t know what loss meant. (And I have learned, over time, that loss is a permanent condition, something I’ve embraced and find acceptable and where I find creativity.) I had to begin a process by which I learned to adjust to what was far away, pushing what was near far – as Solnit says in her second, of three, “The Blue of Distance” chapters. This was an instinct. And in this instinct, there is a cost that lies dormant, waiting its due. Again using Solnit’s helpful language: I did not imagine myself like this, “in this way”; I had to “lose [my] past to join the present, and this abandonment of memory, of old ties, is the steep cost of adaptation.”

In Solnit’s second “The Blue of Distance” chapter, which happens before the fourth chapter, “Abandon,” I’m beginning to understand how essential being lost is to identity formation – and in my case, how being lost in exile begins, first, by a strange and complex mechanism of denial about one’s identity followed, in time and with much experience, with acceptance.

Exile takes a person’s dignity away, says Said. In Solnit’s hands, using the history of the conquest of the New World and the biography of Cabeza de Vaca, we learn how castaways, “strays and captives,” feeling (my italics) that “they were far from home, distant from their desires, and then at some point, in a stunning reversal, they came to be at home and what they had longed for became remote, alien, unwanted.” I feel this. I am this. Solnit continues:

For some, perhaps there was a moment when they realized the old longings had become little more than habit and that they were not yearning to go home but had been home for some time; for others the dreams of home must have faded by stages among the increasingly familiar details of their surroundings. They must have learned their surroundings like a language and one day woken up fluent in them. Somehow, for these castaways the far became near and the near far.

I have laid awake at night longing for the habit of stepping out of my home, at Segunda La Valleja 1120, to meet friends to play soccer on the quiet streets. I’ve experienced liquored moments where I’m fighting to go home, un-accepting of this gringo life. And it all began to fade and I became a stranger to two places – in two places.

Ten years ago, on my 50th birthday, I returned to this now foreign land, Argentina. Immediately the people saw me as un porteño, a person from Buenos Aires. I’m not. I was born in Córdoba – but the Córdobes has a specific accent, very specific tones to his castellano. I lost that when I woke up one day and I was fluent in another language. When I went to Córdoba, I could hardly understand the language. And when I made an emotional walk up the hill to Segunda La Valleja 1120, it looked smaller, less than what I remembered – the palace of my dreams no more. I felt the same displacement as when I first saw my new father in his hospital bed that displaced his own bed.

I felt the exile. I was there, en el barrio Cofico, but not. I was born here, on one of the hottest days, approaching midnight, but I’m not from here. I live in the almighty States but there, according to my NATURALIZATION PAPERS, I was an alien.

The loss I feel is because I’ve had to learn to live in the shadows – an alien, sometimes even to myself. And what I’ve done – and continue to do, I suppose – is to make the shadows, the edges and boundaries of our tenebrous life significant. That’s something, I guess.

Bombay blues

The blue of longing in Bombay is in its waters. In the vast Arabian Sea to the west that meets the city at its southernmost point, Marine Drive. It is my escape. It is my horizon. It is my yonder. It is my edge of the world, and the start of another. I sat there last night talking to N, a friend in another city while waiting to meet R, who was ten minutes away from me, and was struck by two thoughts that Solnit talks about – desire and longing.

“We treat desire as a problem to be solved, address what desire is for and focus on that something and how to acquire it rather than on the nature and the sensation of desire, though often it is the distance between us and the object of desire that fills the space between with the blue of longing”.

It is my blue of longing.

Last night R and I started discussing connection, or the lack of it, that made people engage in one-way interactions seemingly disguised as “conversations” through instant messaging, fleeting interactions and mostly just a desire to be heard above the rest. I am honestly annoyed by people having long conversations over impersonal mediums without bothering to make the time for the same in person. We were both frustrated with how people confuse connectivity with connection and I began thinking about the spaces between us. Virtual spaces are slowly encroaching upon my emotional and physical boundaries to such an extent that I’m made to feel almost wrong for wanting them both simultaneously. Are we so scared to address our desire to connect and sit with that desire and accept it, so much that we make a connection – however fleeting – and then move on as if the desire has been addressed? I leave so many dinners and outings here recently feeling unfulfilled, mostly because they’ve ended up feeling cursory and a lame attempt at a checklist of how interactions should be, and I wish I knew how to change the nature of my interactions with people to a point where every one of them allowed me to lose myself in the other person. I want to not be afraid of depth, and of the unknown and release myself from the shackles of having to arrive somewhere with every interaction. It makes me think of purpose and how purpose is sometimes in conflict with desire. The two sometimes get confused for meaning one and the same thing, but I’m starting to think more about the chicken-and-the-egg with these two concepts. I’d like to believe that the desire to connect is what shapes the purpose of my longing but at times I feel as if the purpose is almost transactional. This then reduces my desire, my longing, to a destination where – once I’ve arrived – I must renounce it. And I’m not okay with that.